Black Requiem – The Masterpiece That Never Was Released (1971, 1988, 1992)

Here’s a great story about a Quincy Jones/Ray Charles masterpiece that was staged twice, and even seriously studio-produced once on location, but that never made it to a release.

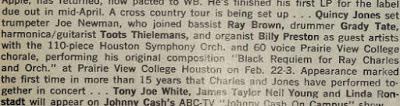

The piece is called Black Requiem or A Black Requiem for short. Billboard, in two brief announcements from 1971, alternatively called it Black Requiem For Ray Charles And Orchestra and Black Requiem (Soul Suite for Ray Charles and Orchestra).

On 20 July 1976 Quincy Jones published a column in The Baltimore Afro-American, where he shed some light on the genesis of Black Requiem, revealing that the work went back on a vow he and Ray made when they were together in Seattle (i.e. 1947/1949):

“Back when Ray and I were just kids, we talked about performing a classical, gospel, jazz and operatic composition together. We even went so far as to vow that one day we would do it. Then in 1971, it happened. As part of the celebration of Ray’s 20th year in show business, we performed my composition Black Requiem with the 80-piece Houston Symphony orchestra. The piece depicted the musical struggle of blacks from the time they entered the slave ships into the period of compensation.

From there it went into the aera of Dr. Martin Luher King Jr., and passive resistance to the period of militancy and lastly, into the era of hope for the future.”

The occasion was Ray Charles 20th show business anniversary in 1971 (that feat had been originally planned for 1969*). It was “an oratorio for full orchestra, chorus, and with Ray Charles as featured soloist”. The event was scheduled for 22 and 23 February and staged at Jones Hall (a venue at the the Prairie View College campus). The dress rehearsal was on the 22nd, the real concert on the 23d.

“It began with the slave ships coming to America and continued through the Watts riots in Los Angeles. Ray was narrator, preacher, storyteller, and participant.”

The Los Angeles Sentinel (Mar. 4, 1971) specified that:

“Utilizing a broad range of musical styles and quotations, Black Requiem made pointed musical references to black slave chants, religious songs, throbbing African rhythms and swinging modern jazz improvisations, all combined and interspersed with symphonic music in a jazz-oriented idiom and occasionally employing avant-garde aleatoric techniques for the choral-orchestral ensemble. Along the wat, the text Charles alternately read and sang made specific references to the death dates of black historian W.E.B. Dubois, Malcolm X and the Rev. Martin Luther King. At the very end, a prayer was read expressing the hope that a new second generation would achieve better understanding among races. […] One of its more individual musical effects included the lonely sound of a microphoned harmonica against a soft background of strings. By and large, it achieved a successful consistency of musical speech among its diverse musical forces. […] There were also several arrangements featuring the famed pianist-singer with a strings and a small choral group from the Prairie View College.”

According to a Billboard announcement (Feb. 6, 1971), the orchestra was the “110-piece” Houston Symphony, along with “the 60-piece Prairie View College Chorale” (another source says 80, yet another source counted 200 performers in total) voices and a jazz ensemble, conducted by Quincy Jones.

The Baytown Sun of 19 February 1971 announced that “a host of jazz greats” would contribute to the concert: Ray Brown (b), Joe Newman (tp), Billy Preston (o), Grady Tate (ds) and harmonica-player/guitarist Toots Thielemans**, adding that “The ensemble of jazz artists will also play various jazz standards and improvisations”. It’s not clear to me if this ‘ensemble’ did really perform.

The concert was part of the “Sound of the 70’s” series, which presented rock, C&W, jazz, traditional and modern in a mix with the Houston symphony, conducted by Robert A. Henry (but Quincy conducted the Requiem part of the program).

The event was a triumph.

In 1972, in a syndicated newspaper interview, Jones revealed that he and Ray had plans to tour with the show: “The composer also plans to do more concerts. With Charles, he has composed ‘Black Requiem’. They have performed it with the Houston Symphony, and will take it to major American and European Cities this year. ‘Doing something like ‘Black Requiem’ requires more than saying ‘I want all these strings playing background for my feedback solo guitar,’ explains Jones. ‘You have to be able to arrange for both the combo and the orchestra. Pulling it off really gave is a good old time – we enjoyed it.'” (Quoted from the Santa Fe New Mexican, July 16, 1972).

But later Quincy remembered that he withdrew Black Requiem because “he wanted to make some changes”.

One of the spectators in Houston was Victoria Bond. In 1988, when she was the conductor of the Roanoke Symphony Orchestra, she invited Ray to perform it again. She then found out that the partiture, and a bunch of accompanying notes were kept by Quincy, in rather a chaotic order. But Quincy also had a recording from 1971, that enabled Victoria to reconstruct the whole thing.

For the performance in 1988, Charles and the orchestra were joined by the 60-member Voices of Roanoke. The piece required a large chorus, preferably black and capable of singing in the traditional gospel style (“They were gleaned from churches all over the area,” Bond said) – for a performance at the Salem Civic Center. Charles liked the result so much that he wanted to record with the same group. “When can we do it?”

Four years later, in May 1992, he brought his own engineer and a “mobile studio fleet” to Roanoke University to record Black Requiem in Radford University’s Preston Hall. The jazz ensemble was formed by Will Lee on bass and Steve Ferrone on drums. “300 people” were involved in total.

The recording went well. Ray planned to overdub and mix his “preacher part” and “some other pieces” at a later date in his Los Angeles studio.

“Everyone expected it to be released commercially when all the parts were completed”, but that “never happened”.

At a later meeting with Victoria “[Ray] had in his pocket a cassette recording of everything put together, and it sounded just fabulous”.

But Charles said there were still some things he wanted to change, and there were some things Jones wanted to change. “And there were still, unfortunately, things left to do when he passed away,” Bond said.

She guesses the recording is in the possession of his estate.

Michael Lydon, in his Ray Charles – Man And Music biography (1998, p. 294 – 5) recaps Ray’s assessment like this: “[…] yet on listening to the tapes, Ray decided that the college chorale lacked the oomph of a true gospel choir”.

Bond blogged her beautiful story here. The part about Black Requiem goes like this:

I met Ray Charles when I was studying composition with Paul Glass. Quincy Jones was studying with Paul when he was composing the “Black Requiem,” an oratorio for full orchestra, chorus, and with Ray Charles as featured soloist. It began with the slave ships coming to America and continued through the Watts riots in Los Angeles. Ray was narrator, preacher, storyteller, and participant. He was satiric, serious, jovial, excoriating. He bantered with the chorus, he shouted, he laughed, he cried. The part was written so that it appeared to be a spontaneous improvisation, but it was actually intricately crafted.

Quincy is an amazing arranger, and had carved an open space for Ray to be himself, around which orchestral colors swirled, chorus singers whispered, cursed, growled, chanted and sang. It was a vast panorama inset with vivid vignettes. I attended the premiere with the Houston Symphony. Quincy conducted, making changes and revisions during the rehearsal much to the chagrin of the orchestra, accustomed to having everything set in place.

Being an improviser and accustomed to sensing new insights on the spur of the moment, he did not hesitate to improve and edit what was on the page; dictating notes, rhythms, and articulations to the musicians in the orchestra. Of course Mahler did this, George Szell did this, Bernstein did this, but most of it was done in advance and written into each part by librarians. Quincy’s purpose was the same as theirs, only his method was more spontaneous. However, the Houston Symphony musicians were not receptive to last-minute changes and became impatient and testy. Quincy took it all in stride, unperturbed by their grousing.

The performance was a triumph. I had never experienced such a large and participatory audience. Their enthusiasm was palpable and interactive, as they communicated and reacted to what was on the stage. Between the two rehearsals and the performance there were a few hours and Ray played chess with Paul Glass. I was privileged to be present during this game, which Ray won. He had a special chess set that had pegs beneath each piece and holes in the chess board, so that he could run his hands across the board without upsetting the pieces. His memory was phenomenal and he was a chess master.

Paul had given him a recording of one of my compositions and Ray told me, “Even I can appreciate that,” meaning that 12 tone concert music (which is what I was writing at the time) was not what he normally listened to. “If you’re a legitimate musician-what does that make me? An out of wedlock musician?” he teased me. He has a sly sense of humor and was not hesitant to speak his mind no matter what the consequences. His taste in music was omnivorous, and he appreciated any style as long as it was communicative, honest and well written.

After that memorable concert, I did not see Ray for many years. I left LA, attended and graduated from Juilliard and was appointed Music Director of the Roanoke Symphony in Virginia. I was invited to guest conduct the Richmond Symphony for a pops concert and the soloist was Ray Charles! I introduced myself, and reminded him about the Black Requiem concert in Houston. “Has that piece been performed since then?” I asked him.

“No,” he said, “Quincy withdrew it and wanted to make some changes.” “Do you want to do it again? I’m now Music Director of an orchestra and I could program it.”

“You’ll have to convince Quincy,” he warned. Quincy lived near my mother in Bel Air, just above UCLA in Los Angeles. Ray gave me his contact information and I called him.

“The score of the Black Requiem is in pieces,” he cautioned. “You’d never be able to figure out how to put it together.” “Is there a recording of the performance?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “I think I can piece it together with the recording as my reference and, Ray is interested in performing it again.” “Come over and see what it looks like before you get too excited.”

My husband and I walked up Bel Air Road to Quincy’s secluded mansion high above Beverly Glen Canyon, where he has invited us to lunch. “Before we eat, let me show you what kind of shape this piece is in,” he said as he walked over to a cabinet and bent down to open the bottom doors. “Here, hold this,” he said to my husband as he reached in and took out some large statues, piling them into Stephan’s arms. One after another, identical, shinny Grammy Awards came out, hidden away. Stephan and I looked at these treasures and marveled at Quincy’s modesty to tuck them out of sight and not blatantly proclaim to the world, “Look what I’ve accomplished!” This was Quincy to a T.

During lunch he told us that when he produced “The Color Purple,” no one thought he could do it because he had never produced a film before. “This was a great position to be in because no one expected me to do well. I surprised them all, because I had had the experience of producing many recordings and the process was the same. So starting as the underdog was a plus!”

After all the Grammy Awards were emptied out of the closet, he pulled out several big boxes filled with sheets of music. We got down on the floor and poured over them. There were notes written on scraps of paper, loose sheets without page or measure numbers. This was going to be a truly daunting task, making sense of the jumble of sketches and finished score pages. But then there was the magical tape! It fused all the disparate elements and provided me with a coherent time line. I told Quincy that I felt certain I could re-assemble the score and parts and make it into performance-ready materials. I begged him to trust me and reminded him of Ray’s eagerness to perform it. Reluctantly he relented. We enjoyed a delicious lunch together prepared by his chef. I could see that he was warming to the idea of resuscitating “Black Requiem.”

When I got home I sleuthed through the boxes, arranging every bit of evidence like Sherlock Holmes solving a mystery. With the tape to guide me I was able to make order out of the seeming chaos and to appreciate what an organized and detailed score Quincy had composed. I marveled at the skill and imagination that went into the creation of this masterpiece, and my excitement grew when I contemplated bringing it back to life.

Needless to say, the Roanoke Symphony board of directors was overjoyed at the prospect of presenting a work of Quincy Jones with Ray Charles as soloist. In addition to the orchestra, the piece required a large chorus, preferably black and capable of singing in the traditional gospel style.

Roanoke had a number of black churches, many with excellent choruses, but few could read music. This did not turn out to be an insurmountable problem, as they were accustomed to learning music by rote. I decided to combine the forces of all the local church choirs and to enlist their choir directors to teach them the music, using the recording as a guide. This took considerable preparation and adequate time needed to be allowed in order to learn and memorize the music. A date was chosen when Ray could fly in, his schedule being a complex time-table of international appearances.

Everyone in the community quivered with anticipation.

Because this work was so precious to him, Ray generously insisted on being at several rehearsals, unlike his normal schedule of one rehearsal and then a performance. After the first rehearsal Quincy called. “How did it go?” he asked anxiously. Both Ray and I assured him that the music was glorious, that all of the pieces fused together into one magnificent whole, and that the orchestra and chorus were up to the challenge.

The local newspaper went ballistic. Every chorus member wanted to have his and her picture taken with Ray. He was patient, professional and overwhelmingly inspiring. No one who worked on that production will ever forget his brilliant performances, at rehearsals as well as at the final concert. The piece galvanized the community and the event. It was a day that no one would ever forget.

Ray was glowing. “I want to do it again and record it. When can we do it?” I was ecstatic. Another date was scheduled and Ray arranged for a truck with the most up-to-date sound equipment and his own personal recording engineer to come to Roanoke to record the “Black Requiem.” We recorded in Radford University’s Preston Hall, building a wooden platform over the seats and setting up the truck with the recording booth and equipment. Umbilical cords of thick wires snaked over the floor and through the hall, connecting the stage and the booth. Ray brought several soloists to the session: Will Lee on bass and Steve Ferrone on drums. They adjusted to the circumstances like true peripatetic professionals accustomed to the ever changing kaleidoscope of performance venues.

Ray shuttled between the stage and the truck, closely monitoring every detail. Balance, clarity, sound quality – nothing escaped his microscopic analysis. I was equipped with a headset, which I positioned over one ear, listening to the musicians in front of me with the other. Unlike the live performance, he planned to overdub his part at a later date.

At one point the orchestra erupted in a chaotic burst of sound during the Watts riot section of the piece. After the last note died away, I heard Ray over the headphones: “I didn’t hear the harp. Was the harp playing?”

Having just been bombarded by brass and percussion playing fortissimo, the gentle plucking of the harp was not a sound I had zeroed into. I asked the harpist and she sheepishly confessed that indeed, she had lost her place and failed to play the last passage. What an ear! We all marveled at Ray the magician, capable of hearing sounds no mere mortal could detect.

The sessions went smoothly and we all spent long hours together, intense and concentrated, punctuated by picture-taking, meals, jokes, exhaustion and elation. Ray, ever the perfectionist, never let a detail escape. “Watch out for Ray – he can be like the Ayatollah,” Quincy had warned. “He can be ruthless and withering in his criticism.” […]The Roanoke University website has another great story, where Victoria Bond is again a spokes woman, The Legend On Campus:

In May 1992, Ray Charles came to Radford University to record A Black Requiem in Preston Hall.

Radford University’s Preston Hall was the setting for Ray Charles’ weekend recording session in 1992. When then-Radford President Donald Dedmon met Charles, he said, “Oh my, if I knew we were going to have a celebrity come in, I would have dressed better.” Charles, blind since he was 7, replied, “Mr. President, to me everybody’s dressed well.”

Joe Scartelli, dean of Radford University’s College of Visual and Performing Arts, was the university’s liaison for Ray Charles’ recording session in 1992. Charles had been upset that a photographer was taking pictures, and Scartelli quickly apologized. “All of a sudden, in an instant, he changed. He said, ‘It’s great to meet you, man. Thank you for doing all this work. We’re really excited about it.’ It was like the picture thing never happened.”Victoria Bond, former conductor and musical director of the Roanoke Symphony Orchestra, invited Charles to perform “A Black Requiem” with the orchestra in the late ’80s.

Ray Charles walked into Radford University’s Preston Hall for a weekend recording session. Then he heard a camera shutter click nearby.

“And he went — he went berserk,” Joe Scartelli said. “He started screaming and cursing like a sailor. And I’m thinking, ‘He isn’t even 10 feet in the door and I’ve already blown it.'”There weren’t supposed to be any photographers at the session unless Charles had approved them ahead of time — and he hadn’t approved any photographers. Scartelli, dean of Radford’s College of Visual and Performing Arts, was the university’s liaison for the project. He walked over to the photographer, who worked for the university, confiscated his film and apologized to Charles.

The university was excited about having him on campus, Scartelli told Charles, and so they wanted to have photos of the event. No one knew about the photography prohibition.

“He was still out of breath from screaming,” Scartelli said. “All of a sudden, in an instant, he changed. He said, ‘It’s great to meet you, man. Thank you for doing all this work. We’re really excited about it.’

“It was like the picture thing never happened.”

But that’s not what Scartelli was thinking about.

“All I could remember was, he just called me ‘man.’ I felt like at that point I had arrived,” Scartelli said. “He was wonderful after that.”

But the university never did get any photos.It was May 1992, and Ray Charles, winner of a dozen Grammys and member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, was in town to record “A Black Requiem,” a Quincy Jones composition written to mark Charles’ 25th anniversary in show business. Charles performed the piece in 1971 with the Houston Symphony Orchestra, an 80-voice choir and a jazz ensemble. Victoria Bond, the Roanoke Symphony Orchestra’s conductor and musical director in 1992, was in the audience.

[…]Bond invited Charles to perform it with the RSO. In 1988, Charles and the orchestra were joined by the 60-member Voices of Roanoke — “They were gleaned from churches all over the area,” Bond said — for a performance at the Salem Civic Center. Charles liked the result so much that he wanted to record with the same group. Four years later, they converged on Radford University along with a jazz group that included Will Lee, then bass guitarist for David Letterman’s The World’s Most Dangerous Band and drummer Steve Ferrone, who flew in from a tour with Eric Clapton for the session.

“It was a massive operation,” Scartelli said. “The stage had to be extended out, oh gosh, at least 20 feet — so far it went past the pit and into the seats. They had to take out the first two or three rows of seats.”

Workers built a plastic glass cube in the lobby for the jazz group, complete with a video screen so they could see what was happening on the stage inside.Charles spent most of his time in a mobile 49-track recording studio parked outside. It was part of what Scartelli called “a small fleet of 18-wheel trucks” and buses gathered outside Preston. Charles communicated by telephone with the musicians and singers inside the hall.

Altogether, Scartelli estimated, nearly 300 people were involved.

Security was tight.“All the entrances on the side and the back were all taped off like a crime scene,” Scartelli said. Security people watched the doors and kept the curious and the media at bay. “Ray was not to be disturbed. There weren’t going to be any interviews. No pictures, anything like that.”

Jeff DeBell was trying to cover the event for The Roanoke Times.

“At some point, I was allowed to see all the singers on stage,” said DeBell, now retired from the Times. “I’m not sure I ever laid eyes on Ray Charles. If I did, it wasn’t for long.”DeBell wrote at the time, “Charles wouldn’t talk with reporters at all, and members of his entourage politely but firmly made certain that no one with a note pad or tape recorder got too close to their boss.”

The orchestra and chorus rehearsed that Friday afternoon and evening.Recording sessions took up most of Saturday and Sunday, stretching past 10 p.m. But it was done. Charles recorded his piano sections there, Bond said, but there are spoken parts to the requiem, too.

“He does a whole preacher routine in it,” she said.

That and some other pieces were to be recorded and mixed later in a California studio. Everyone expected it to be released commercially when all the parts were completed. That never happened.

Bond saw Charles later.

“He had in his pocket a cassette recording of everything put together, and it sounded just fabulous,” she said.But Charles said there were still some things he wanted to change, and there were some things Jones wanted to change.

“So there were still things left to do,” Bond said. “And there were still, unfortunately, things left to do when he passed away. So I don’t know if this recording will ever see the light of day. I certainly hope it does. … It’s a terrific piece.”

Bond is not sure what became of the recording.

“I guess it’s in the possession of his estate,” she said.

*On 8 June 1968 Billboard reported that “[…] Jones is working on an extended blues work for Ray Charles, which he plans to premiere at the Hollywood Bowl next year, the 20th anniversary of the start of Charles’ career.” ** Listen to this.

Comments