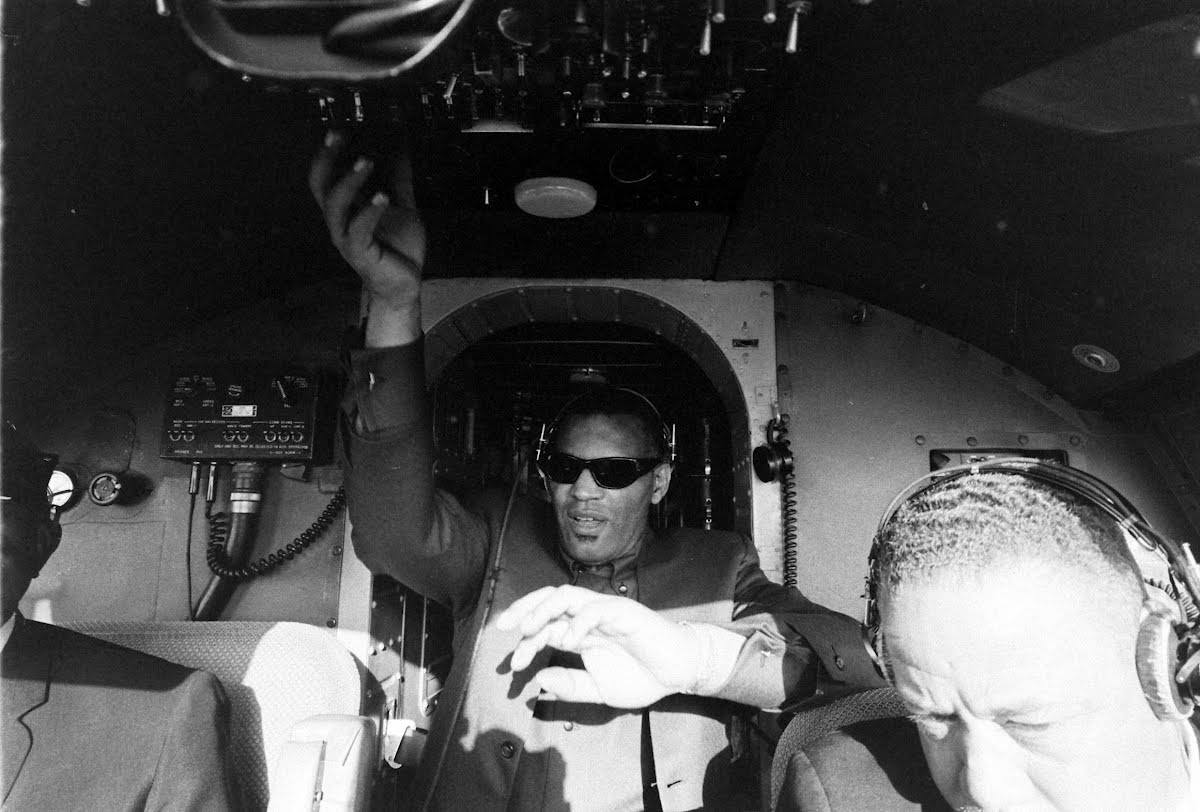

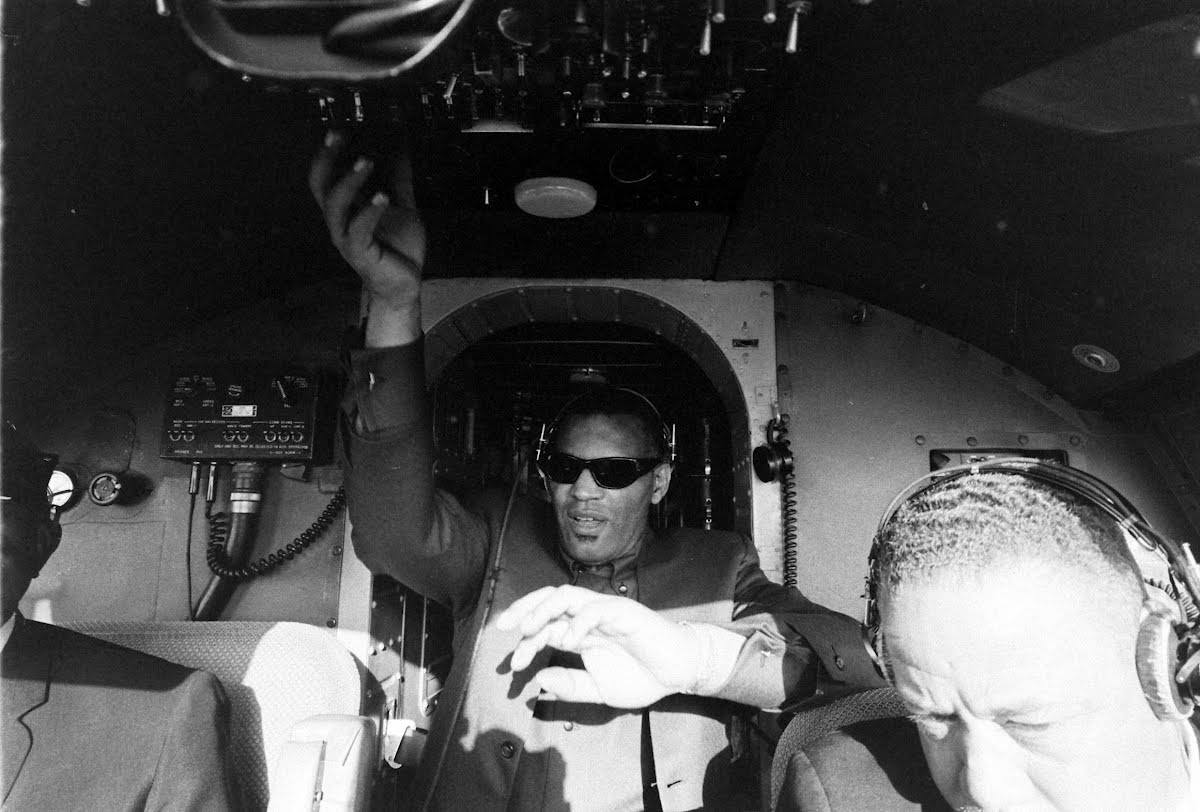

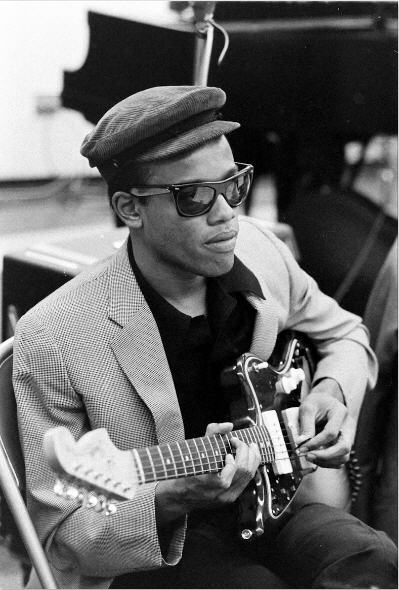

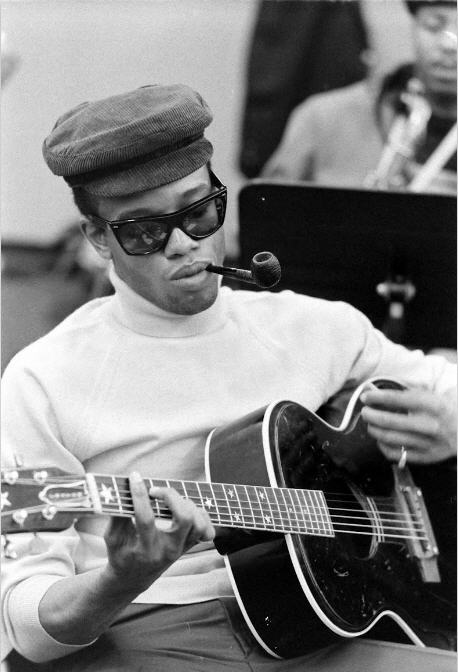

Bobby and Ray (1966)

On May 7, 1966, Ray Charles’ company plane, the Buzzard, carried the complete troupe (1 genius, 4 Raelettes, 16 musicians, manager Joe Adams, a roadie and Ray’s personal assistant) from Los Angeles to New York.

One of the cats in the back of the plane was Bobby Womack. who was hired as a guitar player in the first leg of the Ray Charles 1966 USA tour (which started on March 22 and ended in July). In his biography Midnight Mover: The True Story of the Greatest Soul Singer in the World (John Blake, 2007), he shared a few vivid memories of flying with Ray:

“A blind man playing chess was one thing, but flying a plane – now that was different. The first time it happened it tripped me out. I got aboard the rig we were flying on. It seated about 40 and all the band was there. It was Ray Charles’ own plane and I saw him up front in the cockpit clicking all kinds of switches and flipping buttons.

[…] [A]s soon as we hit the air, the buckle was off and Ray raced up the aisle towards the cockpit. I said, ‘Where’s he going? He never runs like that when he’s going on stage to play the piano.’

The pilot handed the controls to Ray. One of the band filled me in. ‘Ray always takes over the controls.’

That freaked me out. ‘Oh, Jesus me. Dear Lord,’ I prayed. […].”

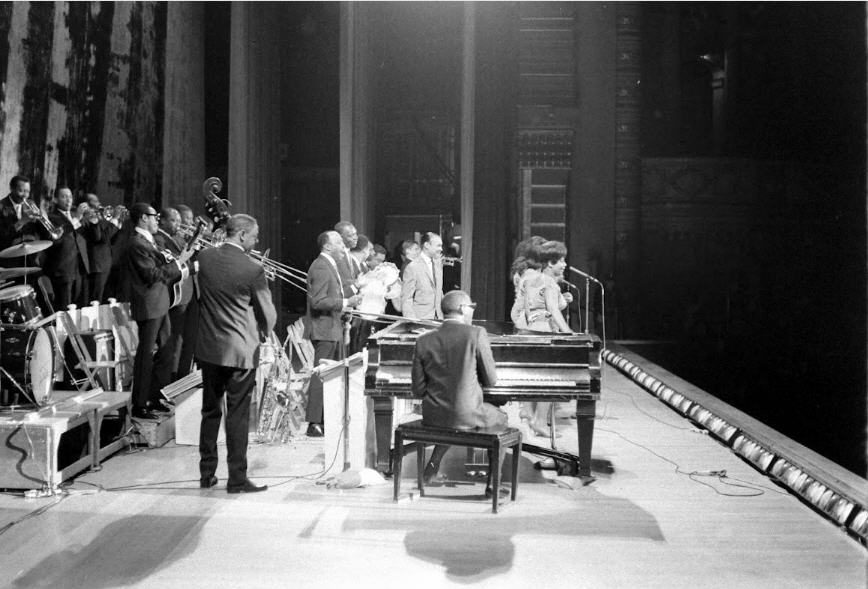

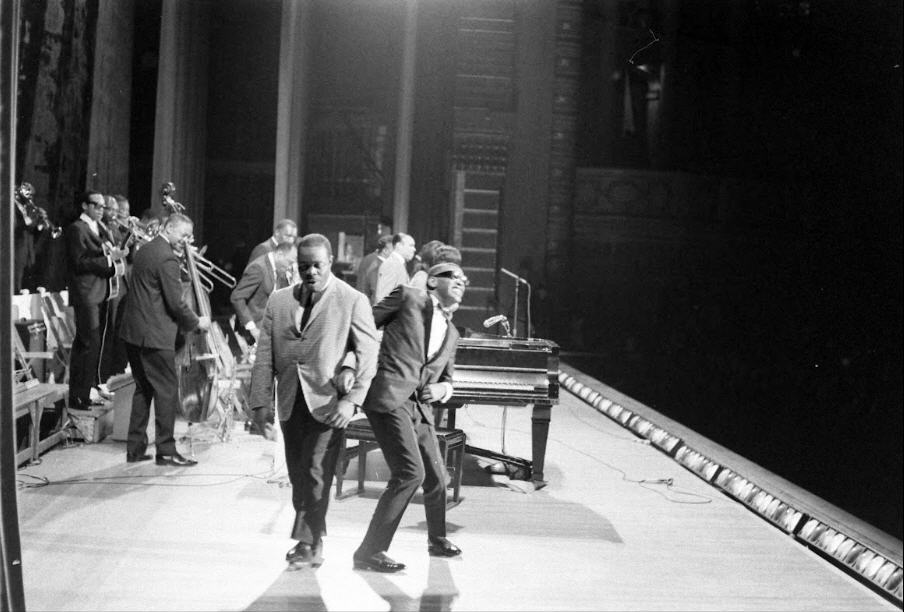

Ray only rarely traveled with the band bus, so the scene in the photo above was probably just staged for Bill Ray’s photo-essay in Life Magazine*, which marked Ray’s actual full comeback after his rehab year in 1965. The Life article was the result of a well planned PR effort to re-position Ray not only as a singer/composer/musician and band leader, but also as an omnipotent record music business mogul and a solid family man. A man who, despite being blind, wasn’t disabled. A man who could “see” and manipulate his environment.

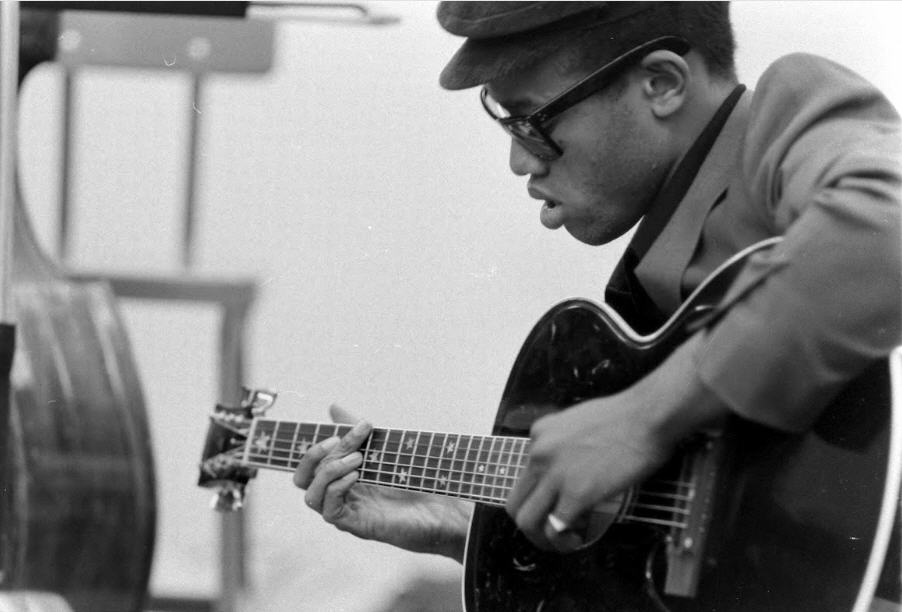

The auditions for Ray’s 1966 “comeback band” probably had taken place by late February or early March. Bobby remembered:

“I sat at the audition with my guitar and a book of music in front of me. The book was about an inch thick. I didn’t open the book. Ray walked in. He shouted out a bunch of numbers, like 48, 92, 31, 15.

Then he said, ‘These are the songs that we’re going to play on these page numbers […]. I still didn’t open the book, just looked ahead – waiting. Someone must have pointed that out. Ray said, ‘You know, young man, you ought to open your book.

I said, ‘I don’t read music, Mr Charles, I play by ear.’

He laughed. Then spat out 31.

[…] I left the book unopened, but joined in. […] Suddenly Ray stopped the band. ‘Second trumpet player. You are flat, tune up.’ The guy tuned up.

Ray kept switching song, going from one number to another, trying to lose me, I’m sure. I kept up. I was in there playing. He stopped the band. ‘OK,’ he said to me, ‘just you and me play.’ Then to the band, ‘See what kind of ears this guy really got?’

[…] He didn’t know how I did it, but he was impressed.”

On March 10 Stanley G. Robertson, staff writer of the Los Angeles Sentinel (and in 1963 freelancing as the writer – assigned by Joe Adams – of the brief biography that was published in Ray’s concert brochures) wrote a newspaper article about attending a ‘sneak preview’ (together “with a cross section of people – college students, selected members of the press, radio, and television professions here, fellow musicians and recording and promotional people, and a few just plain Ray Charles fans”) of “the New Sound of The Genius”.

Adams, who hated all band musicians because they all loathed him, fed the journalist with a few venomous squibs about Ray’s pre-1965 band, plus some erroneous French:

“He has a completely new band. None of the old faces, the stars of former years, such as David ‘Fathead’ Newman, are with him. He has assembled a group of musicians who as a unit sound much sharper and much more cohesive than the old band. As individuals, they possess more enthusiasm, more drive, and more, as the French say, ‘joie de vie’ than did the old group.”

On March 22, 1966 Ray’s ‘new’ band began touring. The line-up was: Steve Hufsteter – lead trumpet; Herbie Anderson, Marshall Hunt, Ike Williams – trumpets; Henry Coker, Sam Hurt, Keg Johnson, Fred Murrell – trombones; Preston Love, Curtis Peagler – alto saxophones; Curtis Amy, Clifford Scott – tenor saxophones; Leroy Cooper – bariton saxophone; Bobby Womack – guitar; Edgar Willis – bass, band leader; Billy Moore – drums; The Raelettes: Gwen Berry, Lillian Fort, Clydie King, Merry Clayton.

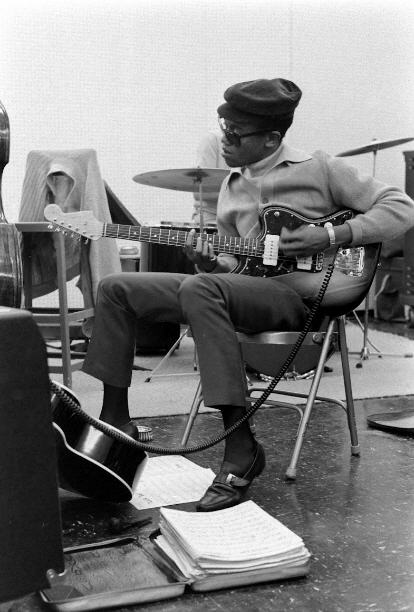

Bill Ray’s Life reportage started at a band rehearsal at Ray’s still quite new RPM International Studio in LA, in March – probably also early that month – 1966.

Bobby’s suit looks good enough on these photos, but in his biography he recalled a previous, more precarious, situation (which was maintained by Joe Adams until the very end of the big band):

“To play in the Ray Charles band, all the new guys had to get themselves kitted out in the house style. Man, that was the opposite of slick.

To save money, the suits were handed down. Every musician who left Ray’s band or retired passed their suit on to the new guy, so these outfits were well past retirement age. They were high water pants, but high water hadn’t been in fashion that century. Also, the last guy who wore my jacket must have weighed 300 pounds. […] It was a whacky mess; the coat was supposed to be beige, but had faded yellow, there were patches in the ass. There were name tags in it going back to the stone age. […] I’d go out front and whisper, ‘Mr Charles, Mr Charles. Can I just sit?’

‘No, stand, young man. Go out there, they like you.'”

Womack was a great musician and a fine storyteller. In the discography added to Midnight Mover he claimed that he had contributed to all of Ray’s 1966, 1967 and 1968 albums (Crying Time, Moods, Listen, Portrait). I doubt if he was consciously lying here, but regrettably probably none of that part of his story was true…

It’s sad that probably nothing of Bobby’s work during his period with the Ray Charles band was ever recorded, not during that tour, not in the studio.

* All photos by Bill Ray; except for the 2nd they are taken from a batch of so far unpublished rest materials from his shoots for the Life Magazine article published on July 29, 1966. The narrative to Bill’s photos was written by Thomas Thompson, Music soaring in a darkened world – The comeback of Ray Charles. Pain and blindness have shaped his genius.

Comments